Arrival was the most underrated sci-fi of the 2010s. Here's why.

Denis Villenevue's masterpiece is not the film you think it is.

After watching the trailer for 2016’s Arrival, you would be forgiven for thinking that the film is a standard sci-fi flick.

Aliens? Check. Threat of global war? Check. A-listers? Check.

The film has all of these things and more, but it’s not really about any of them. What’s Arrival really about? Linguistics. (I can already hear your sighs.)

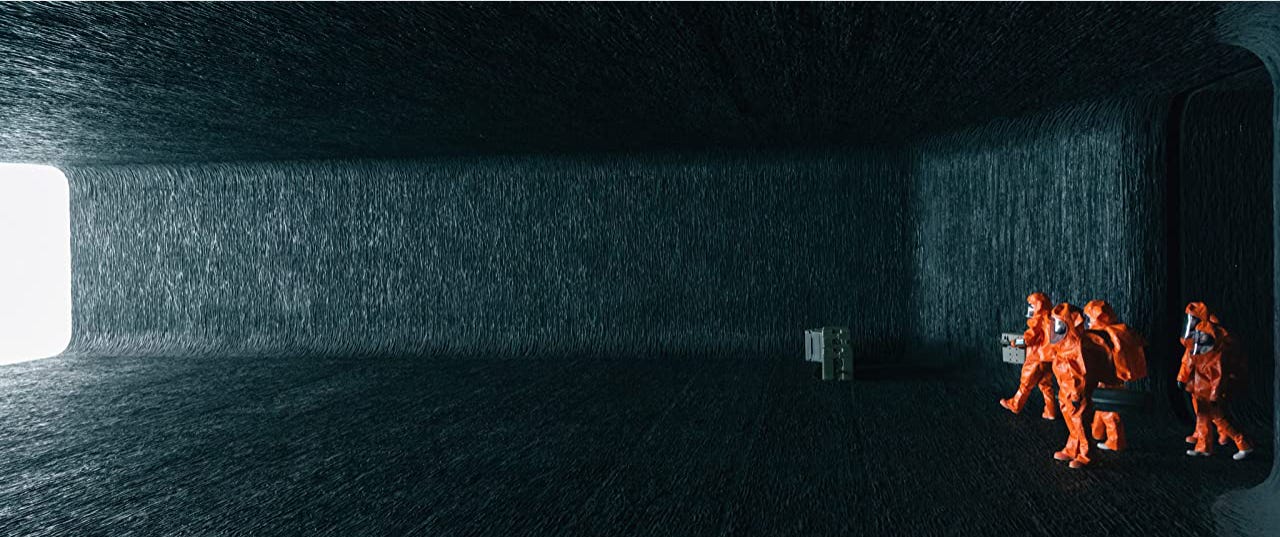

Amy Adams shines as Louise, our protagonist, an academic linguist who is called upon by Colonel G. T. Weber (Forest Whittaker) to investigate and ultimately translate the language of an alien species known as ‘Heptapods’, which has landed on earth in 12 separate spacecrafts. The purpose of their visit is unknown and they appear (to most, at least) to be a peaceful race: the Heptapods fly down to earth and instead of all hell-breaking loose, nothing happens. It is, needless to say, a peculiar entrance.

(Oh, and Jeremy Renner is here too, as physicist Ian Donnelly. He’s fine.)

Louise and Ian lead the American effort to communicate with a pair of Heptapods (affectionately named Abbott and Costello); while this is going on, the threat of global war slowly creeps into view, as geopolitical fractures start to form and communicative barriers begin to crumble.

Aliens, linguistics and geopolitical war: Arrival is not your standard sci-fi flick.

Please, don’t watch the trailer!

“Linguistics, seriously?”

Let’s get this out the way early: a sci-fi about grammar, syntax and communication sounds hard to get right and, let’s be honest, pretty boring.

But somehow, Denis Villenevue manages to make an exploration of language emotional and haunting—by interrogating how and why we communicate (between ourselves and other species), he taps into the idea that we don’t all experience the same reality.

To say any more would breach into spoiler territory: Arrival is a film best seen without any expectations. At just under 2 hours, it’s measured and thoughtful, spending enough time on the fundamentals without overstaying its welcome.

Importantly, these linguistic fundamentals are based on real scientific practices that help lend a more realistic nature to proceedings. Jessica Coon, a linguistics professor who consulted on the movie said, "What the film gets exactly right is both the interactive nature but also that you really have to start small.”

The inclusion of linguistics isn’t just a trivial attempt to be clever; as the film progresses, language becomes the emotional core of the film, uniting humanity and the alien species. Arrival is smart, but it feels earned.

Mesmerising circles reminiscent of splattered ink form the written language of the Heptapods—points of reference are digitally analysed by Louise to create a set of English translations. It’s an incredibly elegant way of conveying the beauty of language while emphasising the scale of the task at hand.

Most importantly to Patrice Vermette, designer of the Heptapod language, these glyphs are completely detached from our languages. The problem, she added, was that these languages are all “part of our history. We can always relate to it. We wanted something totally different."

Linguistics and the nature of language binds Arrival together, propelling the narrative and its characters in a way that subverts traditional expectations of what sci-fi should be.

A final note on music and sound

I would be doing Arrival a disservice if I didn’t briefly mention its magnificent use of sound. The film incorporates an incredible score from the late Jóhann Jóhannsson that treads a delicate line between sound design and song.

It’s one of my favourite scores ever composed and contributes so much to the fabric of the film—voicing the Heptapods where speech is impossible and illustrating a sense of incredible unease, rising and falling with the emotional cadence Villenevue demands. Spliced whale songs and cat purrs are contrasted with choral wailing to create the aliens’ unique sound. That sounds dreadful, but it actually turns out to be weirdly beautiful on screen.

Max Richter’s “On The Nature of Daylight” haunts the opening scenes and provides a backdrop to the most heartfelt aspect of Arrival’s story, Louise’s relationship with her daughter. It’s a piece that is now ubiquitous across Hollywood—in fact, I guarantee you’ll have heard it before—but here it feels like it has been written for the film. It might just be the saddest piece of orchestral music ever recorded.

Although the use of sound is impressive throughout the film, moments that lack a score are often more powerful. “In Arrival, the use of space and silence is extremely important,” Jóhannsson said. “When music is needed, it’s really there and it serves a purpose.” This purpose sets Denis Villenevue’s film apart from many modern blockbusters by training the audience to recognise the importance of sound when it appears, along with the atmospheric impact of silence.

Music shapes our understanding of humans and Heptapods in Arrival and provides an emotional backdrop that we, the audience, can relate to even when the alien language seems so far removed from our own.

While Villenevue’s film is, of course, about aliens (without them we wouldn’t have a film!) it is also, fundamentally, about loss, language and relationships—using its sci-fi premise to explore deeper themes through language and sound.

Simply put, Arrival is a work of art—a stunning experience from start to finish that crescendos to a conclusion so profound and affecting, by the end you realise that you’ve been watching an entirely different film. It’s an intelligent sci-fi, possibly the smartest in years. And it’s definitely the most underrated.